There are several new features in Oracle 12c that are implemented under the hood by changing the SQL statement that we write to a different statement (e.g., by adding some hidden predicates).

In OUG Ireland 2016 I talked about two such features – In Database Archiving and Temporal Validity – as part of my “Write Less (Code) with More (Oracle12c New Features)” presentation. I usually talk about another such feature in this presentation – the Row Limiting clause. This time I skipped it, but Tim Hall talked about it two hours later in his “Analytic Functions: An Oracle Developer’s Best Friend” presentation. Following these presentations I had two short and interesting chats with Tim and with Jonathan Lewis about when, during the statement execution, Oracle rewrites the statements in these features. These chats are the motivation for this post.

When a SQL statement is processed, it goes through several stages, in this order: parsing, optimization, row source generation, and execution.

Note: Parsing is a confusing term, as many times when we say “parsing” (especially “hard parsing”) we actually mean “parsing + optimization + row source generation”.

The first stage, the parsing, is not too complex. The Parser basically checks the syntax and the semantics of the statement. If needed, it also expands the statement. For example, it replaces each view referenced in the statement with its definition, so after parsing the statement refers only to actual tables. Another example: it expands * to the actual column list.

The second stage, the optimization, is much more complex. The Optimizer has several components, and the first one is the Query Transformer. This component may further rewrites the SQL statement that it gets from the Parser, but the purpose here is to find an equivalent statement with a lower cost.

In Oracle 12c we have a simple (and documented) way to see the output of the expansion that is done by the Parser – using the DBMS_UTILITY.EXPAND_SQL_TEXT procedure.

Note: to be more precise, I assume that this procedure reveals everything that the Parser does during the expansion stage, and only that. The documentation of DBMS_UTILITY.EXPAND_SQL_TEXT is very limited. It only says “This procedure recursively replaces any view references in the input SQL query with the corresponding view subquery”, and the Usage Notes imply that it also shows the outcome of applying VPD policies.

Row Limiting

Apparently the new Row Limiting clause, used for Top-N and paging queries, is implemented at the expansion stage. We can see that a query that uses the new Row Limiting syntax is expanded to a pre-12c syntax using analytic functions:

var x clob

begin

dbms_utility.expand_sql_text(

input_sql_text => '

select project_id,

person_id,

assignment_id,

assignment_period_start,

assignment_period_end

from project_assignments

order by project_id,person_id

OFFSET 100 ROWS

FETCH NEXT 4 ROWS ONLY',

output_sql_text => :x);

end;

/

print x

-- I formatted the output to make it more readable

SELECT "A1"."PROJECT_ID" "PROJECT_ID",

"A1"."PERSON_ID" "PERSON_ID",

"A1"."ASSIGNMENT_ID" "ASSIGNMENT_ID",

"A1"."ASSIGNMENT_PERIOD_START" "ASSIGNMENT_PERIOD_START",

"A1"."ASSIGNMENT_PERIOD_END" "ASSIGNMENT_PERIOD_END"

FROM (SELECT "A2"."PROJECT_ID" "PROJECT_ID",

"A2"."PERSON_ID" "PERSON_ID",

"A2"."ASSIGNMENT_ID" "ASSIGNMENT_ID",

"A2"."ASSIGNMENT_PERIOD_START" "ASSIGNMENT_PERIOD_START",

"A2"."ASSIGNMENT_PERIOD_END" "ASSIGNMENT_PERIOD_END",

"A2"."PROJECT_ID" "rowlimit_$_0",

"A2"."PERSON_ID" "rowlimit_$_1",

row_number() over(ORDER BY "A2"."PROJECT_ID", "A2"."PERSON_ID") "rowlimit_$$_rownumber"

FROM "DEMO5"."PROJECT_ASSIGNMENTS""A2") "A1"

WHERE "A1"."rowlimit_$$_rownumber" <= CASE WHEN (100 >= 0) THEN floor(to_number(100)) ELSE 0 END + 4

AND "A1"."rowlimit_$$_rownumber" > 100

ORDER BY "A1"."rowlimit_$_0",

"A1"."rowlimit_$_1"

For more examples like this, and more details about Row Limiting in general, see Write Less with More – Part 5.

Temporal Validity

Temporal Validity allows to apply filtering based on validity period (or range), either explicitly or implicitly.

Explicit filtering is done at the statement-level. Implicit filtering is done by a session-level control.

We can see that both statement-level control and session-level control are implemented at the expansion stage:

alter table project_assignments

add PERIOD FOR assignment_period;

var x clob

begin

dbms_utility.expand_sql_text(

input_sql_text => '

select person_id,

project_id,

assignment_period_start,

assignment_period_end

from project_assignments

AS OF PERIOD FOR assignment_period SYSDATE',

output_sql_text => :x);

end;

/

print x

SELECT "A1"."PERSON_ID" "PERSON_ID",

"A1"."PROJECT_ID" "PROJECT_ID",

"A1"."ASSIGNMENT_PERIOD_START" "ASSIGNMENT_PERIOD_START",

"A1"."ASSIGNMENT_PERIOD_END" "ASSIGNMENT_PERIOD_END"

FROM (SELECT "A2"."ASSIGNMENT_PERIOD_START" "ASSIGNMENT_PERIOD_START",

"A2"."ASSIGNMENT_PERIOD_END" "ASSIGNMENT_PERIOD_END",

"A2"."ASSIGNMENT_ID" "ASSIGNMENT_ID",

"A2"."PERSON_ID" "PERSON_ID",

"A2"."PROJECT_ID" "PROJECT_ID"

FROM "DEMO5"."PROJECT_ASSIGNMENTS" "A2"

WHERE ("A2"."ASSIGNMENT_PERIOD_START" IS NULL OR "A2"."ASSIGNMENT_PERIOD_START" <= SYSDATE)

AND ("A2"."ASSIGNMENT_PERIOD_END" IS NULL OR "A2"."ASSIGNMENT_PERIOD_END" > SYSDATE)) "A1"

> exec dbms_flashback_archive.enable_at_valid_time('CURRENT') PL/SQL procedure successfully completed. var x clob begin dbms_utility.expand_sql_text( input_sql_text => ' select person_id, project_id, assignment_period_start, assignment_period_end from project_assignments', output_sql_text => :x); end; / print x SELECT "A1"."PERSON_ID" "PERSON_ID", "A1"."PROJECT_ID" "PROJECT_ID", "A1"."ASSIGNMENT_PERIOD_START" "ASSIGNMENT_PERIOD_START", "A1"."ASSIGNMENT_PERIOD_END" "ASSIGNMENT_PERIOD_END" FROM (SELECT "A2"."ASSIGNMENT_PERIOD_START" "ASSIGNMENT_PERIOD_START", "A2"."ASSIGNMENT_PERIOD_END" "ASSIGNMENT_PERIOD_END", "A2"."ASSIGNMENT_ID" "ASSIGNMENT_ID", "A2"."PERSON_ID" "PERSON_ID", "A2"."PROJECT_ID" "PROJECT_ID" FROM "DEMO5"."PROJECT_ASSIGNMENTS" "A2" WHERE ("A2"."ASSIGNMENT_PERIOD_START" IS NULL OR "A2"."ASSIGNMENT_PERIOD_START" <= systimestamp(6)) AND ("A2"."ASSIGNMENT_PERIOD_END" IS NULL OR "A2"."ASSIGNMENT_PERIOD_END" > systimestamp(6))) "A1"

For more details about Temporal Validity, see Write Less with More – Part 4.

In-Database Archiving

Tables that are defined as ROW ARCHIVAL have the hidden column ORA_ARCHIVE_STATE. By default, when we select from such tables a hidden predicate is added automatically: ORA_ARCHIVE_STATE = ‘0’.

As shown in Write Less with More – Part 3:

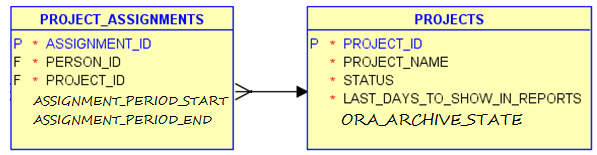

drop table projects cascade constraints;

create table projects (

project_id integer not null constraint projects_pk primary key,

project_name varchar2(100) not null,

status number(1) not null,

last_days_to_show_in_reports integer not null

)

ROW ARCHIVAL;

insert into projects values (1,'Project A',1,2);

insert into projects values (2,'Project B',2,3);

insert into projects values (3,'Project C',1,4);

insert into projects values (4,'Project D',2,3);

commit;

> update projects set ORA_ARCHIVE_STATE='1' where project_id in (1,3);

2 rows updated.

> select * from projects;

LAST_DAYS_TO

PROJECT_ID PROJECT_NAME STATUS SHOW_IN_REPORTS

---------- ------------ ---------- ---------------

2 Project B 2 3

4 Project D 2 3

> select * from table(dbms_xplan.display_cursor());

PLAN_TABLE_OUTPUT

------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

SQL_ID dcthaywgmzra7, child number 1

-------------------------------------

select * from projects

Plan hash value: 2188942312

------------------------------------------------------------------------------

| Id | Operation | Name | Rows | Bytes | Cost (%CPU)| Time |

------------------------------------------------------------------------------

| 0 | SELECT STATEMENT | | | | 3 (100)| |

|* 1 | TABLE ACCESS FULL| PROJECTS | 4 | 8372 | 3 (0)| 00:00:01 |

------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Predicate Information (identified by operation id):

---------------------------------------------------

1 - filter("PROJECTS"."ORA_ARCHIVE_STATE"='0')

But when does Oracle add this predicate?

In this case, it’s not during expansion:

var x clob

begin

dbms_utility.expand_sql_text(

input_sql_text => 'select * from projects',

output_sql_text => :x);

end;

/

PL/SQL procedure successfully completed.

print x

SELECT "A1"."PROJECT_ID" "PROJECT_ID",

"A1"."PROJECT_NAME" "PROJECT_NAME",

"A1"."STATUS" "STATUS",

"A1"."LAST_DAYS_TO_SHOW_IN_REPORTS" "LAST_DAYS_TO_SHOW_IN_REPORTS"

FROM "DEMO5"."PROJECTS" "A1"

A 10053 trace shows that the predicate is not added by the Query Transformer either (which I think is a good thing, as the Transformer should not change the meaning of the query):

.

.

.

******************************************

----- Current SQL Statement for this session (sql_id=dcthaywgmzra7) -----

select * from projects

*******************************************

.

.

.

=====================================

SPD: BEGIN context at statement level

=====================================

Stmt: ******* UNPARSED QUERY IS *******

SELECT "PROJECTS"."PROJECT_ID" "PROJECT_ID","PROJECTS"."PROJECT_NAME" "PROJECT_NAME","PROJECTS"."STATUS" "STATUS","PROJECTS"."LAST_DAYS_TO_SHOW_IN_REPORTS" "LAST_DAYS_TO_SHOW_IN_REPORTS" FROM "DEMO5"."PROJECTS" "PROJECTS" WHERE "PROJECTS"."ORA_ARCHIVE_STATE"='0'

Objects referenced in the statement

PROJECTS[PROJECTS] 113224, type = 1

Objects in the hash table

Hash table Object 113224, type = 1, ownerid = 8465150763180795273:

No Dynamic Sampling Directives for the object

Return code in qosdInitDirCtx: ENBLD

===================================

SPD: END context at statement level

===================================

Final query after transformations:******* UNPARSED QUERY IS *******

SELECT "PROJECTS"."PROJECT_ID" "PROJECT_ID","PROJECTS"."PROJECT_NAME" "PROJECT_NAME","PROJECTS"."STATUS" "STATUS","PROJECTS"."LAST_DAYS_TO_SHOW_IN_REPORTS" "LAST_DAYS_TO_SHOW_IN_REPORTS" FROM "DEMO5"."PROJECTS" "PROJECTS" WHERE "PROJECTS"."ORA_ARCHIVE_STATE"='0'

kkoqbc: optimizing query block SEL$1 (#0)

.

.

.

A 10046 trace file contains no indication for ORA_ARCHIVE_STATE at all.

Comparing 10053 trace files of the statement select * from projects between two executions – one with the default behavior where the predicate is added and the second with “alter session set ROW ARCHIVAL VISIBILITY = ALL” which returns all the records with no filtering on ORA_ARCHIVE_STATE – shows only one significant difference: under Compilation Environment Dump we see that ilm_filter = 0 in the former and ilm_filter = 1 in the latter.

So the predicate on ORA_ARCHIVE_STATE is probably added by neither the Parser nor the Query Transformer. I don’t know who does add it and when, but it seems that it is not done in the “standard” way Oracle usually do such things. Perhaps if it would have been done in the standard way, this bug (look at the “The Bad News” section) would not have happened.